A Prelude of Raincoats, Paper Music, Dreams, and Mini-Dramas: The Forward Opening

Curtain up! Lucerne Festival Forward opens this year inside the Box at the Luzerner Theater. And it’s the perfect venue: to launch our fall weekend devoted to contemporary music, we present five works that explore the charged space between sound and stage, score and performance, tone and body.

Take, for example, Georges Aperghis, who turns 80 in December and taught for many years at the Bern University of the Arts. He has been a decisive influence on the evolution of experimental théâtre musical in Switzerland and beyond. His work Ruinen (1994) is more than a piece for solo tuba (or trombone) but an extraordinarily virtuosic work of instrumental theater. Nervous figures and tension-filled gestures collide with moments in which the performer breathes, sings, or speaks directly into the instrument. The speech grows increasingly intense, erupting in outbursts that call to mind the battle cries of an Asian martial-arts film.

The Brazilian composer Aurélio Edler-Copes, who was born in 1976 and became a student of Aperghis, also had an instrumental mini-drama in mind. In Seul(e) (2009), he explores “an almost theatrical situation in which the harpist tries to say something but never succeeds.” Against a compulsively repeated harp motif – made all the more unsettling by the instrument’s quarter-tone detuning – the performer’s voice emerges: out of breath with agitation, gasping, stammering, singing. “Je voudrais seulement un peu de …” (“I would just like a little bit of …”) is all we can make out before the piece suddenly breaks off.

The three other works on the opening program move even further in the direction of performance art. In Hirn & Ei (2010–11), Carola Bauckholt calls for four percussionists, but instead of equipping them with an elaborate arsenal of instruments, she dresses them in Gore-Tex jackets (she even recommends specific brands). Yet these garments prove astonishingly versatile sound sources: tapped and rubbed, brushed with a phone card along the sleeve, or scraped by pulling the zipper. Bauckholt precisely notates the often complex overlapping rhythms in the score, while also specifying gestures and movements for the performers, giving each rendition a strongly theatrical flair – along with a generous dose of humor. And of course, this “raincoat music” begins with a “Raindrop Prélude,” played on empty tin cans and rubber bands.

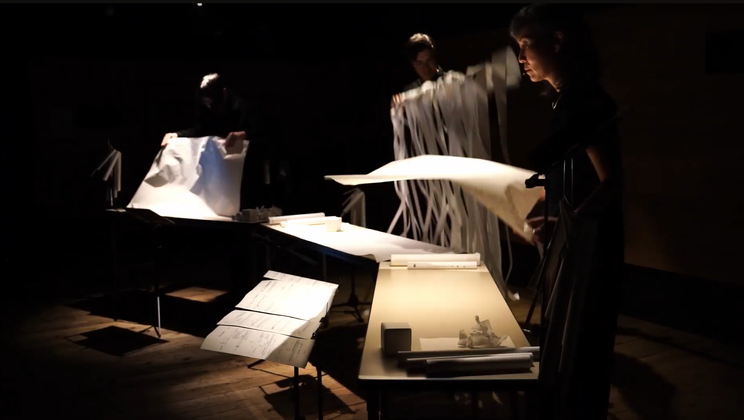

Musicians are constantly surrounded by paper – the sheet music from which they play (even if it’s increasingly being replaced by digital screens). But in Kotoka Suzuki’s In Praise of Shadows, they actually perform on paper. The Japanese-born composer, who teaches at the University of Toronto, wrote this 2015 work for “paper instruments”: flutes and bells, shakers and brushes, all fashioned from paper – with detailed crafting instructions included in the score. The result is a fascinating sonic world of rustles and crackles, “zoomed in” through microphones and enriched by electronic sounds. Suzuki drew inspiration from the 1933 essay of the same name by her compatriot Tanizaki Jun’ichirō. Just as Tanizaki envisioned a distinctly Japanese aesthetics of shadow threatened by the triumph of electric light, Suzuki reflects on the “collective loss of the tangible in our modern life,” which has been brought about by digitalization and virtuality. Using material as actual instrumentation, it highlights “the real world and our presence within it.”

The first world premiere of this year’s Forward Festival, Neo Hülcker’s new work other spaces likewise largely dispenses with traditional instruments. Instead, it takes a performative approach, using the performers’ own bodies – their voices, faces, and gestures – as its medium. The piece explores the peculiar structure of dreams – with their sudden breaks and disjointed turns – but above all dreams as documents of their time. Hülcker found inspiration in Charlotte Beradt’s book The Third Reich of Dreams. Between 1933 and 1939, the German journalist collected the dreams of “every ordinary person accessible to me,” revealing, as Hülcker notes, “how deeply Nazi terror had penetrated every corner of private life.”

Malte Lohmann, editorial

-

Fri 21.11.OpeningDate and Venue

Fri 21.11. | 19.30 | Luzerner Theater, BoxProgram

Bauckholt | Suzuki | Edler-Copes | Aperghis | HülckerForward Festival 2025starting at CHF 50