With two blunt chords from the full orchestra, Beethoven’s Third Symphony– also known as the Eroica – bursts in, all elbows, from the very first bar. The Fifth is no less direct, its famous opening declaring the equivalent of “Here I am”: da-da-da-DAA. But the Fourth steals in almost unnoticed. It opens with an unusually soft pianissimo – something Beethoven does elsewhere in his symphonies only in the Ninth – with a slow introduction that seems to hesitate and wander, feeling its way through one mysterious harmonic detour after another.

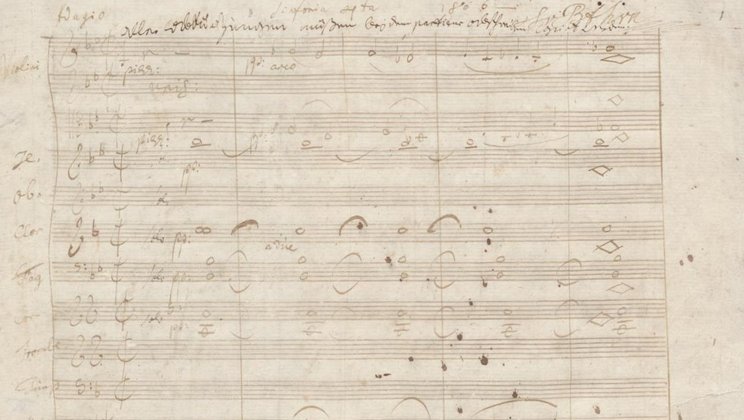

The music holds us in suspense, nothing quite settling. But then, with a sudden crescendo and a series of ever-quickening orchestral blows, the sun bursts out – and from that moment on, the Fourth mirrors the season in which Beethoven began writing it: late summer, 1806.

The music presses forward without pause. The strings whirl, the bassoons skip along in high spirits, while oboe and flute add cheerful birdsong. The finale is pure overflow: a headlong rush of spinning 16th notes that never let up, even pressing the less-agile bassoon into service in a passage bassoonists have long learned to fear.

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony does not celebrate a larger-than-life hero like the Third, nor does it raise a fist against Fate à la Fifth. There’s no overreaching drama, no program, no biographical weight to carry. Instead, it offers sheer joie de vivre and playfulness: quick wit, lightness of touch, and a steady stream of imaginative, tongue-in-cheek ideas.

But that very ease has worked against the piece. This sunny summer symphony has long been underestimated and, in the concert hall, quietly sidelined. Too slight, some say – little more than a passing interlude between the monumental Third and Fifth. Robert Schumann, who in fact was a devoted champion of the Fourth, understood that the “slender Greek maiden,” as he called it, would always have a hard time standing between “two Nordic giants.” Felix Mendelssohn thought otherwise: in 1835, he chose the Fourth for his inaugural concert as Kapellmeister of the Gewandhaus in Leipzig.

More admirers? Franz Schubert was so taken with the harmonically daring of the slow introduction that he promptly copied them out by hand. An echo of this music can be heard in the opening of Gustav Mahler’s First Symphony, which he likened to “the sound of nature.” Leonard Bernstein called the Fourth “the biggest surprise package Beethoven has ever handed us.” And Riccardo Chailly, who will conduct the work on 29 March at the closing concert of our Spring Festival – paired with the equally summery Violin Concerto by the Fourth’s great admirer Felix Mendelssohn – takes the same view, calling it “an irresistible piece, a treasure of beauty from the first to the last movement.” Orchestras have a particular fondness for the work, not least its high-octane finale, which has players leaning forward and giving it everything they’ve got.

In fact, Beethoven’s Fourth ranks among his most demanding orchestral works, calling for a high degree of virtuosity from the players. And yet the first time this symphony was performed, it may have been not by a major city orchestra but by a provincial, amateur ensemble.

In the summer of 1806, Ludwig van Beethoven paid a visit to one of his Viennese patrons, Karl von Lichnowsky, at his estate in Grätz, in Silesia. They took a trip together to visit Oberglogau (nowadays Głogówek), where Count Franz von Oppersdorff resided. A passionate music lover, the Count maintained his own private orchestra, staffed by members of his household, and honored his guests with a performance of Beethoven’s Second Symphony –aptly enough, a work dedicated to Lichnowsky. He even went so far as to commission a new symphony from the composer.

Beethoven completed the Fourth in short order and dedicated it to Oppersdorff in exchange for a fee of 500 florins, which included – standard practice at the time – six months of exclusive performance rights. Yet in March 1807, well before that period had expired, the Fourth was played at Prince Lobkowitz’s Vienna palace, alongside its three symphonic predecessors – a truly mammoth program. It is entirely possible, though, that the Count’s private orchestra in Oberglogau had already played the work by then. Whether that ensemble was fully equal to the formidable demands of the score is, of course, another question altogether.

As it happens: the Fourth Symphony clearly struck a chord with Franz von Oppersdorff, who promptly commissioned Beethoven for another work and even paid two advances on the fee. Beethoven, however, strung him along and then sold off his Fifth Symphony to Breitkopf & Härtel, without ever refunding Oppersdorff the money.

Malte Lohmann (translated by Thomas May)

-

Sun 29.03.Lucerne Festival Orchestra 2

Lucerne Festival Orchestra | Riccardo Chailly | Emmanuel Tjeknavorian

Date and Venue

Sun 29.03. | 17.00 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

Mendelssohn | Beethoven